Henry Hodsdon and his 'Marble' Totalisators

Bob Doran

Introduction

Although it was known that there had been 'marble' totalisator machines in Queensland made by Henry Hodsdon, they tended to be treated as somewhat of an object of amusement by later commentators:

We in Australia have also had our share of crudely run totes, an interesting one being the old 'marble' tote used in Brisbane in earlier days. With this marble tote, the ticket seller operated a machine which, when a particular horse was selected, produced a pre-printed ticket on that horse and dropped a marble into a special marble race for that horse number. ... Old timers can still recall one of many costly errors which was made when a cockroach died half way along the winning horse’s marble race during betting and most marbles on the horse were blocked by the cockroach’s prostate body! (Courtesy Mervyn Smith.)

On odd occasions a match or debris would find its way into the marble tracks resulting in a blockage. The cry 'Bank up' would go up, alerting special 'marble boys' who armed with torches would locate the problem, clear the debris and try to ease the passing of the heavy balls. If they lost control as happened many times several hundred ball bearings would gather speed and crash into the cellar counting room and scatter everywhere, causing many educated guesses and head scratching as to what the total should have been. It has been said that the overall noise level in the tote caused by thousands of balls on the move was something to behold. (Courtesy Brian Conlon.)

The survivors write the history! In actual fact, looking into the records, Henry Hodsdon and his company successfully operated most of the totalisators in Queensland for 50 years. He and his machines were certainly not regarded as a joke during his lifetime.

Outline of Henry Hodsdon’s career

Henry Hodsdon was born in West Ham near London in 1860, where he was still listed in the 1881 census as a carpenter. He emigrated to Queensland, along with three of his brothers, John, William and Alfred, sometime before he was married in 1888 in Brisbane to Alice Morley. It is thought that in Queensland he initially worked with his brother John on constructing railway carriages.Henry, known as Harry, had a head for invention. His first patented device was a machine for starting horse races. He then turned his attention to improving the operation of totalisators, which were in widespread use in Queensland. He developed his first machine during 1897, placing it into use on 12-13 August 1898. He founded Hodsdon Totaliser and Enumerating Machines Company around the same time. His company, which designed and operated totalisators, was a family business involving his brother John, his wife, sons and nephews. In his wife Alice's obituary in 1932, she is credited with management of the totalisator operation in her husband’s absence.

Hodsdon totalisators spread quickly throughout Queensland. As well as in Brisbane Hodsdon had machines operating in Toowoomba, Charters Towers and Ipswitch by 1902. It seems that most of the important race courses in Queensland had Hodsdon totalistors at some time — in addition to those already mentioned, there were Hodsdon machines at Rockhampton, Warwick, Charleville, and at the gold-mining town of Croydon.

Hodsdon marketed his machines elsewhere. He demonstrated then in Western Australia, though with no sale, and his most important sale outside Queensland was to Port Adelaide in South Australia in 1902. This went through multiple upgrades, as did most of his machines. A Hodsdon machine was also sold to a rural course at Gawler in South Australia in 1922. Hodsdon’s brother William moved to Adelaide and may have been involved in operating the family business in South Australia.

Outside Australia the only sale of Hodsdon equipment that is known was in 1908 to the Western India Turf club at Poona. Hodsdon’s brother John and John’s son William went to install and manage the operation of the machine in India.

In Brisbane Hodsdon totalisators predominated. There was a brief flirtation with an ATL machine at Eagle Farm, but when the new pony track at Doomben selected their machine in 1933 Hodsdon's became the only game in town. Henry Hodsdon retired in the 1930s to play bowls, contented that his machines faced no competition in Queensland. He died in 1939 but his machines continued in use until after the second world war, some until the mid 1950s.

The totalisator environment

To appreciate Hodsdon's achievements one has to understand the state of the art at the time. Originating in Paris in the 1860s, the concept of the totalisator had arrived in Australasia by the late 1870s. Rather than being presented as an approach to gambling (the pari-mutuel method) it was associated with machinery used to keep track of totals; indeed, in Australasia the totalisator was always referred to as a machine regardless of how it was implemented.The first machines down under were of German origin, but they were soon manufactured locally with various improvements. They were typically the size of a large up right piano. They were very simple, merely comprising a display of the total number of bets on each horse and the grand-total number of bets on all horses for a race. The operators would accept bets from punters and register the bets one-by-one on the machine. The punters could estimate the expected return for a bet by mentally dividing the horse total into the grand total.

Betting using the totalisator machine immediately became very popular and spread quickly throughout the colonies. Special race meetings of low quality were set up specifically to give more opportunities for betting. This popularity caused alarm to bookmakers, racing clubs and those opposed to gambling. This immediately led to legislation restricting the totalisator. The restrictions ranged from a complete ban — in Victoria and NSW — to giving the right of totalisator operation to genuine racing clubs only; the exact details varied from colony to colony.

Where the totalisator was permitted it grew and grew in popularity, so that the crowds wanting to place bets could not be accommodated by a single machine. One approach taken to deal with the demand was to have more and more machines — there are records of eleven being operated at one track in New Zealand — and this multiple machine approach was also taken in Queensland. But it was not very satisfactory: each machine had different totals and would produce different dividends.

The ideal would be one machine showing the combined bets for all the clients at the racecourse. But this faced a serious technical problem, in dealing with simultaneity. It is easy to increment a counter, one unit at a time, but how could machinery deal with the problem of many punters betting on the same horse at the same instant — and, even worse, incrementing the grand total to show all the bets being made at any instant?

There was no obvious solution to this problem. In some of the colonies, South Australia in particular, a work-around was instituted and a special building was constructed to enclose the machine. There was one ticket-selling window for each horse and the bets for that horse were displayed above that window. There was no display of the grand total — so placing an extra mental-arithmetic burden on the punters. This approach was unsatisfactory for that reason alone, and also because the queues for bets on the favourite horses were longer than the others and created a bottleneck.

The problem with simultaneity is to ensure that all bets are registered and that none are lost. The eventual mechanical solution using a chain of differentials was proposed by Sir George Julius and implemented by his company Automatic Totalisators Limited, and was gradually refined over the years. Hodsdon had a simpler idea which involved separating the issuing of tickets from the counting of bets. When a ticket was issued, a marble or metal ball-bearing would be released — one marble for each bet, so that each bet had a physical representation. The marbles for each horse were then counted by being routed to a separate counting machine for each horse; this had a capacious input hopper but counted serially at speed.

Operation of the Hodsdon totalisator

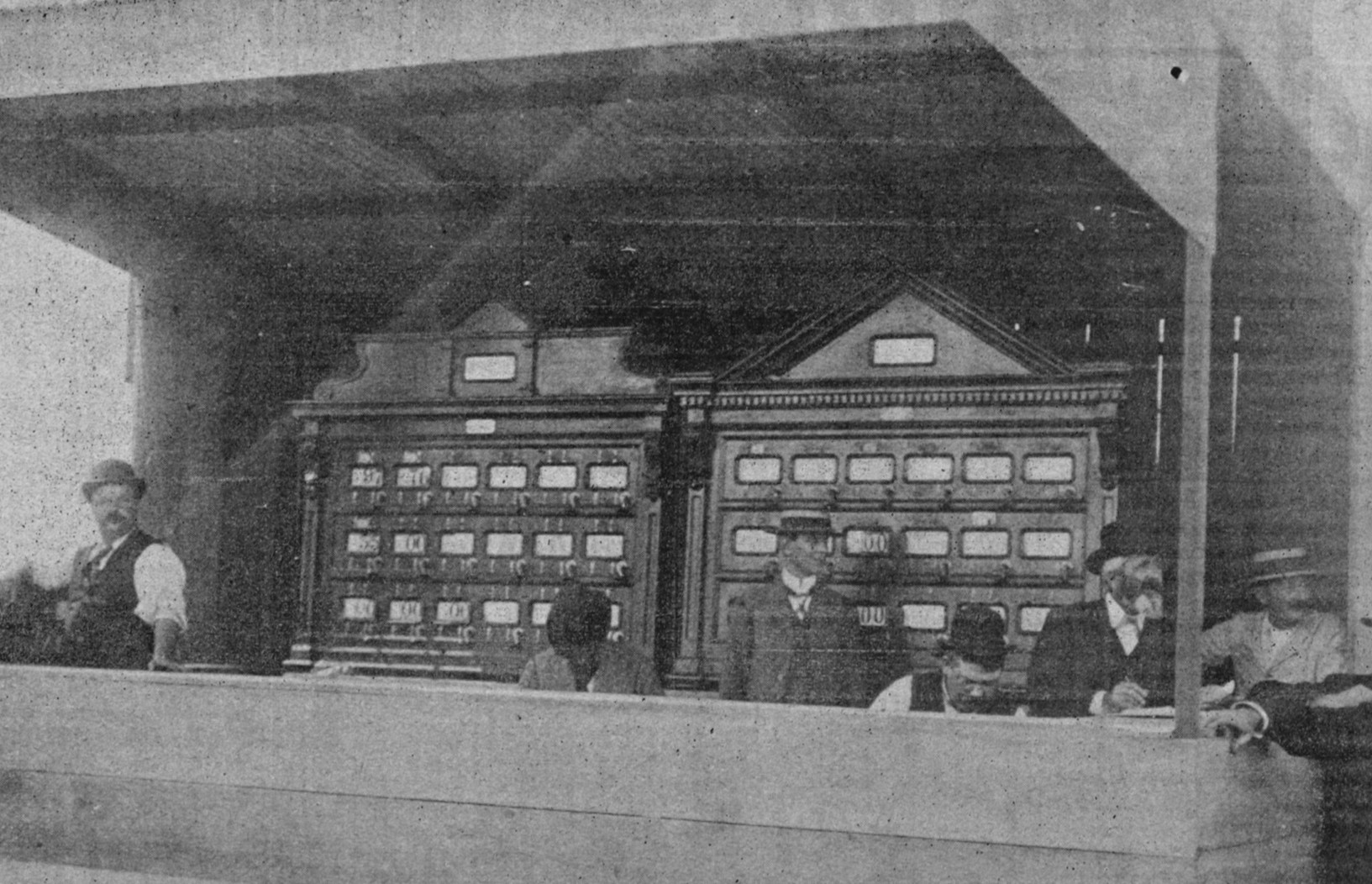

Looking at the early patent claims filed by Hodsdon, he initially applied his idea to the grand total only, with just one unique ticket issuer and counter for each horse. He quickly realized that the same idea would allow every ticket station to sell tickets for every horse — the marbles were routed to a counter for a particular horse but then routed on to another counter for the grand total.Although we have no relics of Hodsdon’s machines there are some photographs and patents from which we can describe the operation in outline. The Hodsdon Patent totalisator was enclosed in a rectangular building constructed for this purpose. It had a number of ticket issuing windows on both sides, a totals display at one end, and some separate 'plain' windows for paying-out dividends.

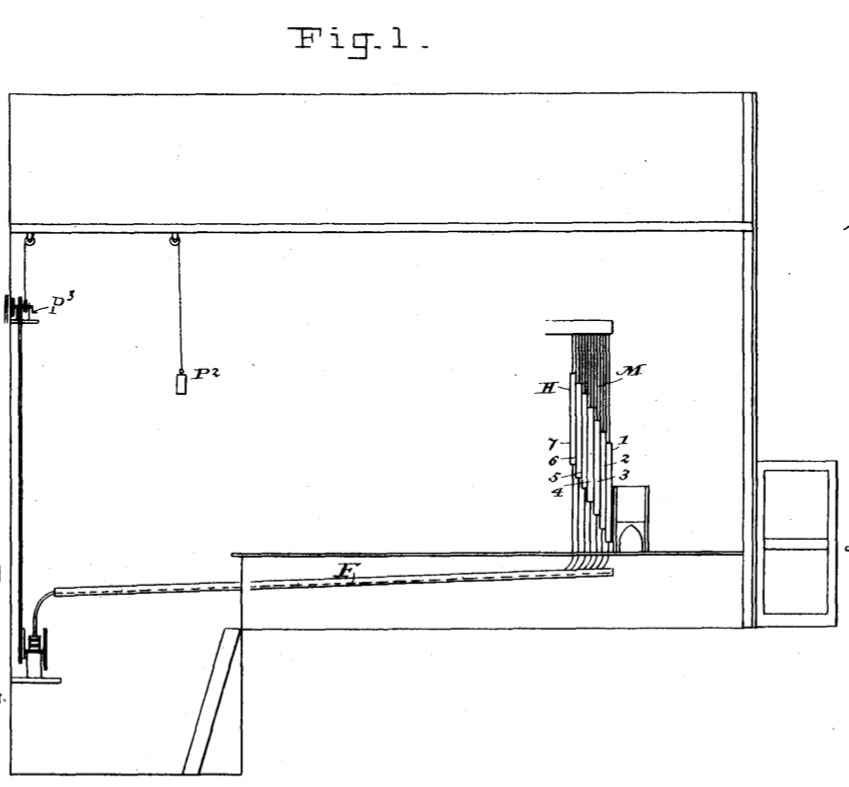

Each ticket-issuing window was equipped with a number of vertical metal tubes, with a ticket issuer and handle attached to each tube — one tube and ticket issuer for each horse. The tickets were pre-printed on moderately thick card and stacked into the ticket-issuer hopper. The tubes were all kept full of marbles, these being loaded into the tubes from hoppers in the loft space that were filled by hand. When a bet was made, the operator pulled the lever for that horse, causing a ticket to be pushed out from the bottom of the stack, and, at the same time, one marble was allowed to fall down the tube to be counted. There were mechanical interlocks to ensure that it was not possible to issue a ticket without releasing a marble, and vice versa.

Next to the ticket issuers was a window through which the punter would ask for the ticket, provide money and receive the ticket and the change. We do not know what was printed on the tickets. However, to counter fraud the tickets must have had some design unique to the race meeting and carried the race number, the horse number and probably a serial number.

The marbles for each horse were routed to the counter unique to that horse. The marbles rolled downhill to the end of the building (a slope of 17 degrees was specified in a later patent.) It is likely that smaller tubes from each window connected to larger races that were open channels rather than tubes. It was necessary to place the mechanism for the counters in a pit at the end of the building in order to get an adequate slope for the furthest sales window.

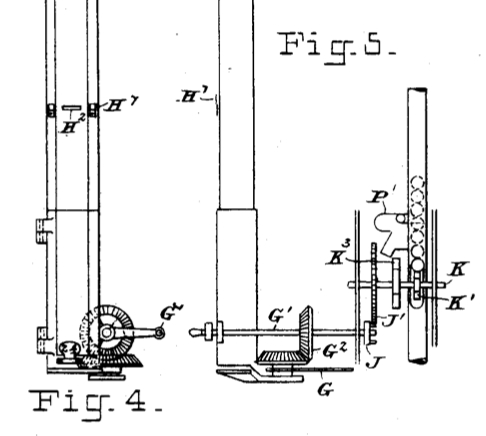

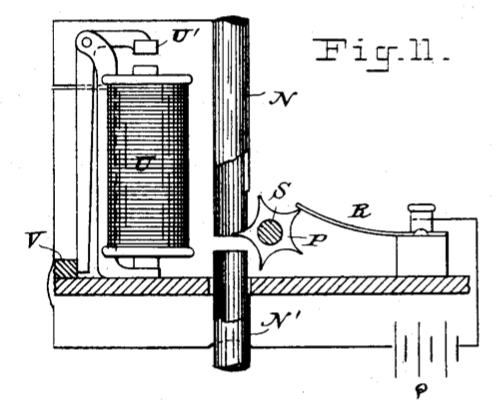

The counters were simple carry propagate incrementors — initially drums displaying digits and later discs of lower mass. The counters were driven to increment by a weight that was raised before each race, and were restricted from advancing by an escapement.

The counters were displayed high up on the building, yet the marbles rolled down low. Hodsdon’s first machines used electricity to increment the counters — each marble, as it passed a star wheel, would make/break a circuit that would operate a solenoid to release the escapement in order to allow the high-up counter to advance. This must have been unreliable, and later machines had a mechanical connection from the marbles that passed upwards to the counter.

After being counted for a horse total, the marbles would be routed further down to an input hopper for the grand total counter (which operated in a similar manner). The marbles were then collected in a bin and manually lifted up to fill the input tubes to the ticket issuers.

Performance of the Hodsdon machines

The concept is very simple but how well did it work? There must have been many practical problems to overcome such as marbles becoming jammed in hoppers. One general 'solution' was described in Hodsdon’s 1912 US patent detailing improvements: this was the introduction of a human attendant to the mechanism. The attendant had the specific role of starting the counters and applying brakes in order to make sure that they did not accelerate or decelerate too abruptly — but the attendant could also deal with other problems as they arose.

All the same, it is apparent that the Hodsdon machines did not always operate perfectly. The South Australian Argus gives an interesting account of the introduction of the Hodsdon machine in 1902. It was, initially, a disaster when the batteries that operated the circuits counting the marbles failed. There was a call for the machine to be abandoned, but Hodsdon, who was managing the installation himself, worked steadily to regain the public confidence. He succeeded to the extent that his machines remained in use for over 40 years in Adelaide.

Even though the machine worked adequately, the newspapers reported that problems remained. Often the sum of the horse totals did not quite match the grand total. The grand total counter could not keep up in real time and continued counting after the tote was closed. The counting mechanism must have caused difficulties for a long-time — Hodsdon replaced the electrical connection with a mechanical one early on. But the problem persisted and the slowness of the grand total was still being discussed in the 1930s, although as a 'feature' rather than a 'bug'.

The totalisator had interlocks, claimed to be 'almost infallible', ensuring that the tickets issued and the marbles released were in a 1-1 correspondence. However, if any marbles got mixed up (as described in the introductory quotes) there was no way of dealing with the problem, since the marbles for all horses were identical. One might wonder how a machine that was not 100% accurate could be so highly regarded.

The answer was that the precise accuracy of the displays was not really important. They were used to give an indication to the punters of what returns to expect. If the grand total was slightly off, it didn’t matter much to the punters’ decisions. The same applies to the totals for favoured horses, and the totals for outsiders were so small that their counters could probably cope. With later ATL totalisators the displays of actual numbers were replaced by 'barometer' indicators showing expected dividends for a unit bet, or, equivalently, the rough odds being offered. The barometers could not be read precisely and were always claimed to be only approximate or indicative.

What was very important, however, was that accurate totals were maintained by some means, so that the dividends — and more importantly the overheads retained for the club — could be calculated precisely. This became even more important when totalisators were taxed and inspectors kept oversight to ensure that the returns to the state were correct.

Hodsdon machine totals were not accurate enough to be relied upon for precise calculations, as was the case with later ATL machines. One can only deduce that there was some other way of checking the totals. In New Zealand, and elsewhere, it was shown that large totalisators could be operated with no calculating or totaling machinery by using serial numbers on the tickets. Something similar must have been used by Hodsdon. We know that the tickets sold were pre-printed, so providing simple serial numbers would allow accurate totals to be calculated once betting on a race closed.

In addition, we have to conclude that Hodsdon and his company must have been very good at managing the totalisator operation. No matter what machinery was provided, if the process were not well managed it would be possible to make mistakes or create unacceptable delays while the dividends were reckoned. Hodsdon’s totalisators maintained a reputation for smooth operation.

Hodsdon Totes at Eagle Farm

Hodsdon’s first and most prestigious site was the Queensland Turf Club’s course at Eagle Farm. The sequence of changes made there over the years illustrates the way that Hodsdon’s totalisators were improved.

Hodsdon’s first totalisator house (1898) at Eagle Farm was destroyed by fire in January 1913. It was immediately replaced by a much larger and fancier building with more ticket sale windows. We do not know much about this second Hodsdon machine, since 1916 the operation of the totalisator was given to a different local company, which installed a Julius machine instead. This was Julius’s third machine, following Auckland and Perth, and was very like the Auckland machine except for using electrical power and interconnections. It is thought that the new non-Hodsdon machine used the Hodsdon totalisator building, but extended with a second story.

Hodsdon and his supporters protested this decision through the newspapers — Hodsdon’s company even ran a full-page advertisement from which we can learn a lot about his machines. The main question asked was why the change was made. The answer seemed to be that the Julius machine was considered much more modern, and made use of electricity:

In these advanced days, when almost everything is run by electricity, especially where speed is required, one would fancy that the Hodsdon machine would be electrically controlled. It is nothing of the kind. Mr Hodsdon gave up electricity long ago.

Certainly the Julius machine would have appeared more impressive, and, if it was properly operated, could provide totals with no delay and did not need pre-printed tickets (although ATL, in listing its machines later, always noted that this Brisbane machine did not use ATL-recommended ticket issuers). It is likely that punters would have noticed very little difference in functionality, though there were in fact many initial complaints about the new machine.

The contract for the Julius machine was for seven years. As the time approached for renewal, there were rumours of ATL attempting to buy Hodsdon’s Totalisator company to eliminate competition. At any event, the contract was renewed, with Hodsdon shut out of his home turf once again.

In 1926, however, the State suddenly revoked the license of the ATL totalisator, because of operational problems. Hodsdon, who had continued operating at other racecourses, stepped into the breach, running a totalisator without displays on a temporary basis. His company was once more given the contract to operate the totalisator at Eagle Farm. The existing building seems to have been radically modified, with the display placed at the other end of the building.

The Hodsdon totalisators were gradually exposed as lacking functionality in comparison with their competitors. Hodsdon’s disdain for electricity made it difficult to provide remote ticket-selling stations and remote displays. From the mid 1930s, mechanical totalisators offered displays of expected dividends rather than totals. Manual totalisators quickly followed this lead — indeed the Adelaide Hodsdon machine had a manually operated barometer display appended.

So it was not unexpected that the Hodsdon totalisators were phased out. The Hodsdon machine at Eagle Farm lasted until 1949 (just over 50 years since the first installation), when it was again replaced by the latest ATL Julius machine. The building was once more extensively modified, with the ATL machine occupying a second story and with barometer displays in two directions and two blocks of remote ticket-issuing stations. The final machine lasted until replaced by computer systems. The building, with its retained ATL machinery upstairs, is still there as part of a museum.

Assessment

Hodsdon’s was the first of four Australian companies known to have exported totalisator machines. His totalisator was the first in Australasia to have a dedicated tote house for the whole course that maintained full displays of horse totals and the grand total. Hodsdon’s 1898 tote was a model for such tote houses in other places, even if they did not use machinery. It seems likely that the rash of such 'machines' in New Zealand (starting in 1901) and elsewhere was inspired by Hodsdon’s example.

Often it is said that the 1913 Julius installation at Auckland was the first automatic totalisator. Whether this is an accurate claim does depend on what is meant by 'automatic'. There was an Automatic Totalisator Company registered in Queensland in 1890, but this was automatic only in that the tickets were printed by the machine. In fact, no totalisator machine was truly fully automatic until computerization — for example, none of the electro-mechanical machines could subtract in order to deal with late scratchings. If one compares the functionality of Hodsdon's 1898 machine with Julius's 1913 machine they are almost identical (the Julius was of larger capacity, but the Hodsdon 1913 models were too). What was different was that Julius’s first machine formed a basis for development and could be extended with new technology (ticket-issuing machines that printed, for example). Hodsdon’s approach eventually fell behind, but it was a notable achievement nonetheless.

We hope that some relics will turn up to enable us to describe the Hodsdon machines in more detail. In any case, this is not the end of the story of marble totes — another Australian company used a marble-based machine, the Lightning. This company was the first to install a totalisator machine in New South Wales, in 1917, and was marketing as far away as the UK. This is another chapter in the totalisator story.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to: Brian Conlon and Mervyn Smith for the anecdotes regarding the marble tote; and Jan Massey and Wendy Whitehead, descendants of John Hodsdon, for providing photos of the Hodsdon family and copies of early patents. A great deal of information was gathered from newspapers searchable on-line, both Papers Past in New Zealand and the Australian National Library.